Z niecierpliwością czekam na relacje wspomnianego świadka.

Bardzo podoba nam sie podejscie kol. Baniaka - o to chodzi! Zrodlo z 1 reki samego zainteresowanego. Reszta to materialy poboczne.

Widze ze kolega od p. Godziny pelen dobrych checi "uprzedzil" ale jak sam zaznaczyl na szybko - wiec byle jak. Tradycyjnie tez, bo niejako w roztargnieniu i zapomnieniu bo mial wspomniec ale jakos wczesniej zapomnial

Dwie rady dla amatora historyka:

1. Aby udowodnic teze historyczna nie wystarczy skan 1 str z 1 ksiazki (do tego z 1 zrodla) vide Battalion.

2. Potrzeba tez troche pokory i cierpliwosci. Posluchac do konca to co ktos ma do powiedzenia i dopiero pozniej ewentualnie dzielic sie takim strzepem informacji

P.s. - jak koledzy ze 101 beda zainteresowani (nie chcemy przeciez balaganic na formum) - to przy okazji i kufelku mozemy rozwinac temat szerzej

A teraz juz obiecane txt z roznych zrodel:

1. Len Goodgal, 101st Airborne Division

On D-Day I got wet. They hit my plane going over; we went over the coast. I remember going over, I was looking out. I could see the sea.

I could see the coast from where I was in the plane. I was looking out the door. The door was open. When we went over the coast the door

was open. It was a beautiful night. Twelve o’clock, 12:30, something like that. We went over the coast, all of a sudden, Christ, there

was anti-aircraft fire, and fire, we could see it on the ground, in the air, in the sky. And the plane got hit in the tail. At least

we’re ready to jump. The plane got hit in the tail and went into a dive. I just stood there hanging onto my static line thinking I was

gonna get killed. I didn’t really think of anything but hanging in there. And it pulled out of the dive. When he pulled out it went up a

little bit, and the lights – when it went down it turned the lights red instead of green, or yellow. Then they turned it back to yellow.

I went around and got back in the door. "Everybody get ready to go!" Boom! All of a sudden we left.

We got hit again, in the right side. I didn’t know where. The fellow that was No. 2, Nils Christensen, told me that the right wing

was on fire. He could see out there better than I could, that the right engine was on fire. We must have gotten hit in the right engine,

and it was tilted that way. We were coming out the other way, so I just about got out of the plane. I was the last guy out. I was the

fourth man, and the last guy out.

I had a lot of equipment on.

The plane was going down. I knew it was going down. I didn’t know where it was. I knew the plane was hit and it was sinking, not too

rapidly either. [Only four guys got out of the plane.] Two of them landed on top of the cliff, and two of us landed in the water. Me and

another guy landed in the water, and two landed on the cliffs. One of them was Nils Christensen who was captured. Another one was

Lieutenant Johnson, who got hurt, and got back to the outfit somehow or other and was evacuated. But Nils Christensen spent ten months in

a prisoner of war camp.

I hit the water. I didn’t know whether I was going to drown or what. I landed right on my back almost. I took my chute and snapped it

off, got out of my stuff and got my rifle, which I had strapped across me. My equipment was underneath the chute when I got up.

I started to swim, but when I stood up I was only in about a foot of water. The other guy was calling me. In fact, he was saying, "Is

that you, Sam?"

I said, "Yeah!" My middle name is Samuel, all the guys called me Sam.

He said, "Where are we at?"

I said, "I wish I knew. I hope this is the White Cliffs of Dover," because I saw those goddamn cliffs. How are we going to get up

these sonofabitches? So we went under the cliffs looking for where the hell we were. We didn’t have any maps, nobody told us about those

cliffs or anything else.

So we worked our way along the shore. We couldn’t find a way up. We tried to get up one place, it looked like we might be able to get

up, but we couldn’t. We got down a little further, and they were bombing; the bombers were dropping 2,000 pound bombs all night long. And

the Navy was shelling the cliffs. We actually put our gas masks on, and the canisters didn’t work, we couldn’t breathe. Because I smelled

the powder; I thought it was lewisite gas, which smells sweet. I figured maybe we’re being gassed with that powder burning when it hit

the cliffs. What the hell’s going on? And we didn’t know. We threw the gas masks away because they didn’t work.

Raymond Crouch is the guy who was with me, Raymond L. Crouch from Richmond, Virginia. He was a sweetheart of a guy.

In the morning, early, we see these boats coming along the cliffs. I said, "Hey, maybe they’ll come in and get us."

Well, as we walk along, all of a sudden they’re coming in and assaulting these cliffs, firing the toggle ropes up and all that. These

guys are running and jumping and going like crazy, and on top of the cliffs they’re cutting the ropes, firing down, and throwing grenades

over the side. We’re down there and the colonel’s motioning for us to come over. Colonel Rudder has died since then. He was a nice guy.

No Ranger ever got the Congressional Medal of Honor, but he deserved it. He was recommended for it.

I didn’t have a high regard for the guy until that happened. Then I realized what they had done.

The guns were not in place there. Guys tell me they were back in the woods, and that they put grenades in there to burn them out. But

I recall seeing two guns along the road, two big long guns. They didn’t look burned out to me. I saw two of them. Maybe they were. They

were camouflaged. I thought that’s what they were gonna use up there in those emplacements, the gun emplacements, but at the time we

didn’t know. We really had no idea what it was. I didn’t know what I was going for. I didn’t know I was doing up there after I got up

there.

The next day – the first day I saw a lot of ships out there, but the second day it was a sea of ships. You couldn’t see water

anymore. Just a sea of ships like foam churning on the water. All you could see was the battleship Texas, which was our artillery. A

couple of little destroyers. And then there was a sea of ships, all white. You could not see the water past where the ships started. It

was like that for a couple of days. So you know if they had those guns up there, the damage they could do. You couldn’t see Utah Beach,

it was too far. You couldn’t see Omaha Beach to the right, it’s too far. All I saw was cliffs. What a bitch. Those guys really were

heroes themselves because they knew what they were going for. I was just incidental. They could have been giving out candy bars up there,

what the hell did I know was up there.

They threw everything over the goddamn cliffs. They didn’t start really getting at us until we started getting up there. As we came

up they became aware, but if that thing had been heavily defended, nobody could get up there. And the other thing was, once we got up

there, everybody had a B.A.R., a machine gun or something. I picked up a tommy gun. Who the hell wants a rifle? You’re firing away at

everything you can see. Some of these guys had to attack pillboxes to get them out.

We were up behind a pillbox. The colonel was with us. We were getting fired on. They needed artillery support, and they wanted the

Navy to fire over that point. They wanted somebody to go back and get the flag that was hanging over the cliff, but who’s gonna go? I

said, "Okay, I’ll go." So I went to get the flag, which was hanging over the cliff. I got the flag. I got fired at going out to get it

and coming back. The colonel commended me highly for going and doing it.

The ships could see the flag and use it as an artillery point, and know where we were, and fire beyond it. We needed it.

The ships were our artillery. We had a Naval observer with us who came up with a radio. We used the radio to tell them where to fire.

The casualties were so heavy, all we could do was just sit in there and hold on till they broke through to us.

Guys got heads blown off. Broke a leg or arm falling off the cliff. We had prisoners underneath the cliff that they sent back by

boat; they brought in a boat, I don’t know whether the Navy sent it or it was a boat they brought in, to take them back. We didn’t want

to keep them there, the German prisoners. For three days we were just getting prisoners. In back of us. They’d pop up, you didn’t know

where they came from.

They’d usually surrender. They knew how to surrender. They’d unbutton their overcoats and throw their helmets and rifles away. I

never caught a German soldier with his helmet on unless it was right on a foxhole or something had happened. Otherwise they knew how to

surrender. They’d take their helmets off, unbutton their overcoat and throw their rifle away. They’d say "Kamerad, Kamerad."

Some of them were Germans, but there were also Polish. There was a Polish battalion of workers that were there to do that work. They

were helping to build the fortifications. But they had German uniforms, green uniforms, Wehrmacht.

They didn’t seem that young to me. Most of the soldiers that I saw looked like battle-hardened guys, or had been around a while. Or

they were like engineers’ workers, they could have been any age. They weren’t that old.

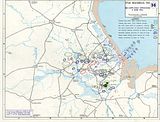

2. Raport

"The report (MACR)on the other aircraft, plane # 733 shed new light on exactly what happened aboard this aircraft. Damaged by anti-

aircraft fire the pilots struggled for control of the aircraft. The pilot missed dropping troops on the first pass on DZ D. Out over the

Channel the Jumpmaster, 2nd Lt. Floyd R. Johnston requested that the pilot, 2nd Lt. William H. Zeunar of the 97th Squadron make another

pass on the drop zone. Heading back over the coast the ill-fated craft again came under fire, probably from shore batteries. This time

around an engine erupted in flames and the aircraft was quickly going out of control and losing altitude. In a steep dive four of the

paratroopers were successful in a struggle against the G-forces and exited the plane, one was Jumpmaster Johnston who broke his arm and

was eventually returned to his unit. Another trooper was captured by the Germans and two lucky paratroopers who got out of the plummeting

plane landed in waist deep water off of Pointe-Du-Hoc. When the Rangers made their assault on Pointe-Du-Hoc later in the early morning

the two troopers joined the Rangers and the two 101st men fought over the next days along side the Rangers."

Pozdrowionka

P.s - a tak jeszcze przy okazji

glupot ktore piszesz:

Pierwszymi żołnierzami U.S. Army na Pointe-du-Hoc byli Sgt. Leonard Goodgall i Pvt. Raymond Crouch z kompanii I, 506

A gdzie reszta? Bo wedlug naszej wiedzy bylo ich 4. Ech..

Wczytujac sie w relacje weteranow 2 Batalionu Rangers-ow natrafilismy na ciekawa historie i zdjecie

Wczytujac sie w relacje weteranow 2 Batalionu Rangers-ow natrafilismy na ciekawa historie i zdjecie  Jak ktos zna te historie - na razie zeby nie smiecic zamieszczamy zdjecie

Jak ktos zna te historie - na razie zeby nie smiecic zamieszczamy zdjecie  Jutro jak szanowni koledzy chca zamiescilmy krotka relacje swiadka tamtego wydarzenia. Tymczasem zdjecie

Jutro jak szanowni koledzy chca zamiescilmy krotka relacje swiadka tamtego wydarzenia. Tymczasem zdjecie  http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a4/Soldiers_resting_at_Pointe_du_Hoc.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a4/Soldiers_resting_at_Pointe_du_Hoc.jpg

?

?